Bacterial Blight of Cotton Update: July 13, 2012

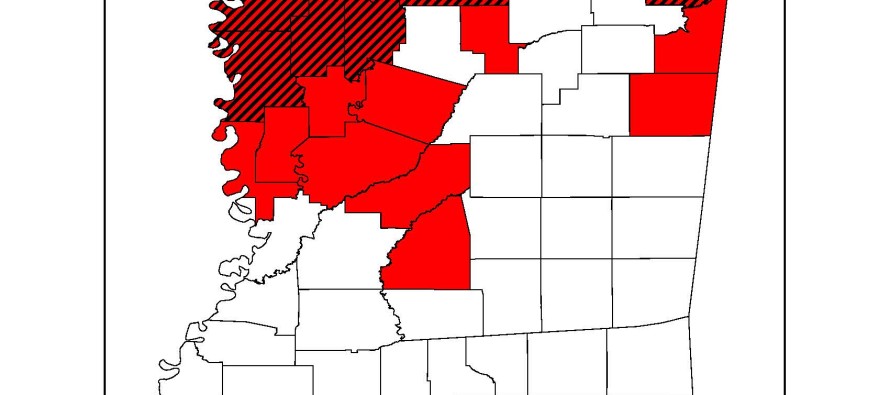

Once again, as in 2011, we are faced with unanswered questions regarding a plant disease that was almost eradicated through seed sanitation practices during the 1970s. Almost 30 years have gone by since the last epidemic caused by Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. malvacearum (Xam). Typically, if bacterial blight is encountered in a cotton field during a particular season, only a few leaves or bolls are observed to be infected. During 2011, bacterial blight was confirmed in 11 counties and observed on 5 varieties. In 2011, bacterial blight was only observed in two fields south of Highway 82 (one each in Sunflower and Washington counties). However, this year bacterial blight has either been confirmed by field visits or from photographs in 23 counties (some of which had the disease last year) and on 7 varieties.

2011 infected varieties observed:

DPL 0912

DPL 1028

DPL 1034

ST 4498

ST 5458

2012 infected varieties observed:

DPL 0912

DPL 0935 (one field)

DPL 1028

DPL 1034

DPL 1048

PHY 499

ST 5458

Keep in mind, that the majority of the varieties planted in MS are considered to be susceptible to bacterial blight. However, with that statement in mind in no way are we suggesting that every acre of susceptible cotton has been infected by the bacterium. The only conclusive way to determine if a particular field has infected plant material is through careful scouting.

Facts regarding the disease

-Bacterial blight is a disease that requires an initial source of inoculum for infection to occur. Unless a field has been in cotton production for a number of years and the disease has previously been identified the organism doesn’t have a point source for subsequent infection. In those situations where cotton has either never been planted in a particular field or the field has been out of cotton production for a number of years then the initial source of the bacterium is believed to have been from infested seed. Even though the spread of the organism within a particular field can occur from wind-blown rain, heavy winds, or hail the organism is not able to spread long distances on wind currents as other plant pathogens.

-The bacterium can only enter the plant through natural openings or wounds that can be created by heavy rain, hail, wind damage, equipment damage, herbicide injury, or (in more rare situations) insect injury. But, as with other plant diseases, stressed plants are more likely to not only become infected (if a source of inoculum is present) but they are also more likely to express the disease symptoms. Even though points of injury are more apt to allow the bacterium to enter the plant a source of inoculum needs to be present within the field (see above and read below regarding the ability of the bacterium to survive).

-Xam can move throughout the plant in a systemic fashion.

-Few additional hosts for the bacterium exist. In fact, most research literature suggests that even if the bacterium can infect additional hosts the specific race/strain within a given geographic location may only be able to infect cotton and not close relatives.

-Xam is not able to survive in soil for long periods of time. The majority of the research conducted on the ability of the organism to survive in soil in the absence of host plant material (cotton stubble), in sterilized soil, or in the presence of other plant material suggests great variability in the length of survival in the absence of cotton. We do know that the bacterium can’t survive on the residue left in the field from a non-host (e.g. corn, soybean). However, it is possible (although incredibly unlikely) that Xam could have survived the winter on cotton stubble left in a field that had been in cotton last year and particularly where tillage was not conducted.

-A single infected plant in a cotton field has the ability to create widespread disease within that particular cotton field if a conducive environment occurs. Thus, a single infected seed, planted in a field that germinated and did not die due to the organism while a seedling that now expresses the watersoaked angular lesions on leaves (or any other particular symptom of the disease) has the ability to infect cotton plants in that field.

One interesting issue of note has to do with the area used for inoculation trials conducted in Stoneville last year. Following the 2011 season the field was subsoiled, and disked during the fall, with beds formed in late winter. Cotton was replanted in that particular field in the 2012 season. No bacterial blight has been identified in this particular field and susceptible varieties are planted.

Management suggestions

-Understand that chemical control methods to manage the disease once observed are not available.

-Cotton planted in irrigated fields should continue to be irrigated regardless of the irrigation method employed.

-Don’t change the particular management strategies employed to properly manage the cotton crop. Rank cotton growth could (and we say could here since no reliable data are available) tend to increase the infection that occurs in the canopy. Therefore, application of a plant growth regulator should be conducted as normal. While some have mentioned that reducing plant height by use of high rates of PGR and attempting to promote air flow through the canopy might be considered methods to prevent disease spread, allow the plant to compensate for any infection that may have occurred.